Lost? Not Really: How digital maps keep us found and found us, too.

Because nothing says “I have my act together” like broadcasting to the world where you had avocado toast, all without looking like total narcissists (well, most of the time).

Let’s be honest: humans have always tried to make sense of space. Whether we were etching trails in dirt or pinning brunch spots on Google Maps, we've long wanted to know not just where we are but what matters there. Maps were never just functional. They’re cultural artifacts, showing us what people chose to remember. A holy site. A pizza joint. A war. A weekend getaway. In that sense, today's digital maps are like selfies of society.

For most of history, maps were reserved for the powerful. Explorers, empires, clergy, colonizers. The printing press helped democratize access, but it was GPS, smartphones, and social software that gave maps to everyone. Suddenly, anyone could leave their mark. We weren’t just on the map; we were part of its source code. And we didn’t just use maps to go places we used them to document who we were while being there.

Social apps that use geolocation are the natural evolution of this habit. From prayer flags to check-ins, the human impulse to say "I was here" hasn’t gone away, it’s just gone digital. But these apps do more than map our movements. They help us navigate relationships, identity, nostalgia, even belonging. Sometimes they help us meet up. Other times, they quietly shape how we think about time, space, and ourselves.

This is an attempt to trace the cultural journey of location-based apps: what they enabled, what they ignored, and what we can learn from the trails they left behind.

The 2000s: Maps Go Mobile, Social, and Kinda Weird

The early 2000s were weird. Flip phones seemed fancy, Facebook was still crawling out of dorm rooms, and "checking in" still meant getting to the airport early. But a new type of behavior was beginning to emerge: what if your phone could tell people exactly where you were, in real time?

Enter Dodgeball, born in 2000 out of NYU. It let users blast their location via SMS to friends in the city. It was spontaneous, scrappy, and full of promise. Google acquired Dodgeball in 2005. But instead of scaling it, Google folded it into Latitude in 2009, which introduced gamification elements like leaderboards, then later into Google+, and eventually Google Maps, where location-sharing exists today. So technically, Dodgeball never truly died. It just evolved. This is a recurring pattern: standalone location apps often get absorbed as features inside larger ecosystems, their DNA living on while their brands disappear.

Meanwhile, Dodgeball's founder Dennis Crowley wasn't done yet. In 2009, he launched Foursquare. This time, the hook was gamification: check in, earn points, unlock badges, become mayor of your local dive bar. Foursquare leaned hard into making location fun not just functional but creating a competitive social layer that made sharing your whereabouts addictive.

It's important to remember that early GPS adoption faced significant hurdles. Data plans were expensive, continuously using GPS heavily drained phone batteries, and processing location data consumed a lot of RAM. This made the idea of a "Zenly kind of thing," with constant real-time location sharing, impractical. Apps like Foursquare and Dodgeball relied on periodical check-ins, a solution more manageable given these technical limitations.

Around the same time in Austin, Josh Williams launched Gowalla, a beautifully designed, collectible-driven social passport. It was whimsical, beloved by the design community, and for a brief moment, it felt like the future. But when Facebook and Twitter added simple location-tagging in 2010, these standalone check-in apps lost their edge. The innovative became commoditized overnight.

By 2011, Gowalla was acquired by Facebook. Foursquare, seeing the writing on the wall, split into two: the Foursquare City Guide and Swarm for check-ins. Brightkite, Loopt, and others followed a similar arc - launched with ambition around 2004-2005, scaled for 4-5 years, acquired around 2009, and then either shut down or integrated into larger platforms. The pattern was remarkably consistent.

Was it a hype cycle? Probably. But that's true of most tech. New features often arrive as dedicated apps before becoming invisible infrastructure. These early location pioneers weren't failures so much as necessary first experiments. With GPS technology becoming widely available, someone had to test what people wanted from location sharing. These apps put themselves up for a quick, public death but paved the way for tremendous learning.

The question remains: what does a location-based app need to provide to survive as a standalone product rather than becoming a nested feature? Was it privacy concerns? the "creepy factor" when location sharing was misused that prevented mainstream adoption? Interestingly, these same concerns have persisted through the decades, yet location sharing itself has become ubiquitous, just packaged differently.

These early apps tested boundaries, exposed limitations, and helped define what location-based social could be. They didn't just die, they evolved into the location infrastructure we take for granted today.

The 2010s: From Check-ins to Connection

The 2010s marked a shift as the giddy, gamified check-ins of the early days started feeling a bit… much. As the novelty wore off, location-based apps began maturing into something more useful, more subtle, and far more integrated into the rhythm of daily life.

Recognizing the dwindling appeal of digital mayorships, Foursquare performed its famous pivot around 2014. Dennis Crowley, reading the room, cleaved the check-in feature off into the separate Swarm app, attempting to reposition the main Foursquare app towards local search and discovery. This essentially marked the end of the badge-hunting era and the beginning of location needing to prove its utility.

Meanwhile, Facebook and its enormous user base too helped move things along. Features like Places (launched in 2010) and Groups (relaunched with local organizing tools) began embedding location into how we planned everything from knitting circles to fantasy football leagues. It was less about broadcasting your every move, and more about using maps to coordinate with people you actually knew.

But another type of coordination was picking up steam: meeting strangers offline. This is where Meetup exploded. While Facebook Groups helped existing communities meet offline, Meetup specialized in helping people find new ones altogether. From 8 million users in 2010 to over 25 million by 2013, Meetup proved that location wasn’t just an add-on; it could be the nudge that turned digital interest into real-world belonging.

And then came dating.

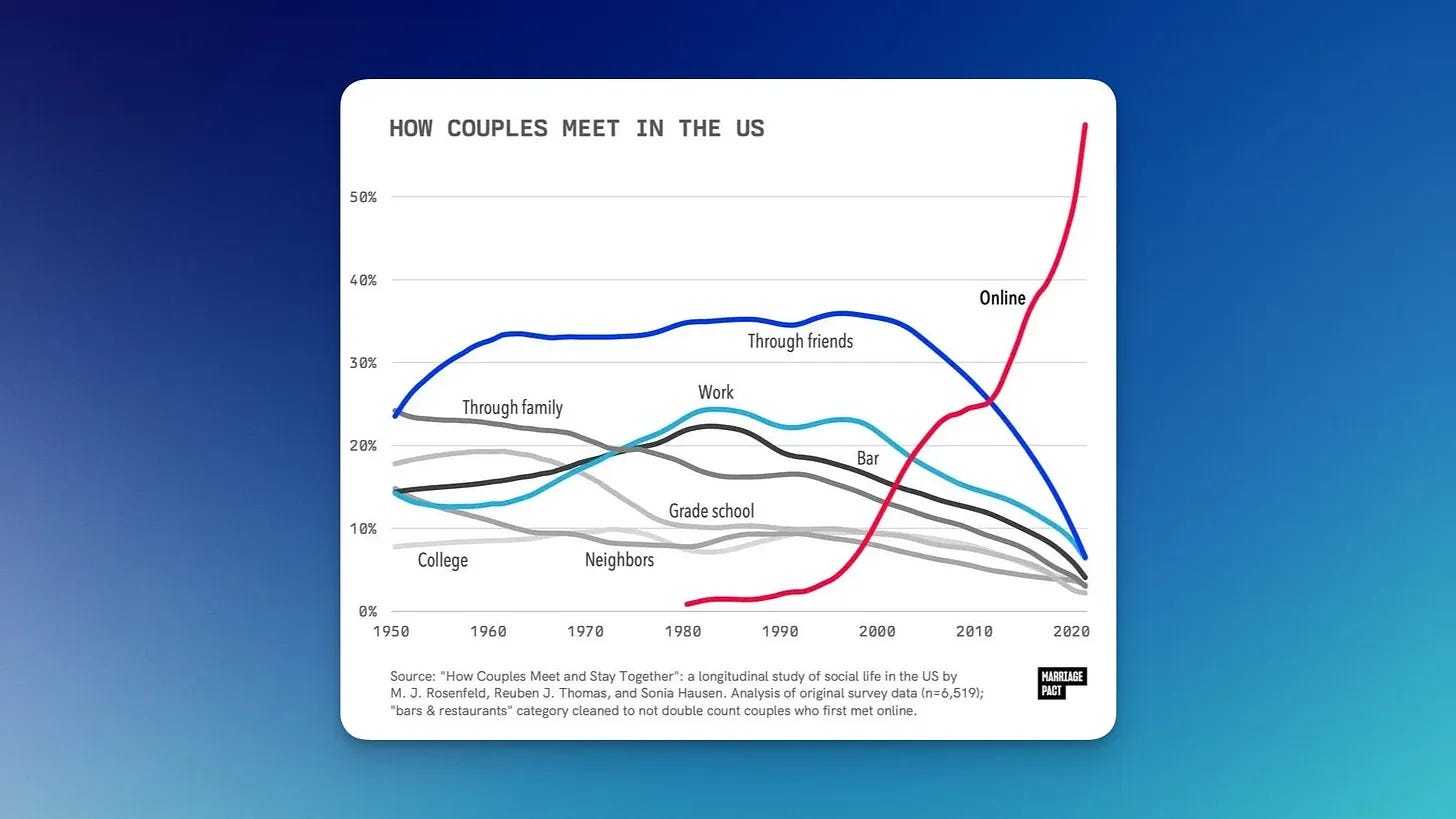

Sure, dating apps already existed. But they weren't built with proximity in mind. Swiping through profiles of people who lived in other time zones was becoming exhausting. The real unlock? Who’s nearby? That’s where Grindr stepped in quietly in 2009, building for gay and bi men with GPS baked in from day one. Then Tinder arrived in 2012, adding its now-famous swipe mechanic and turning proximity into ‘propinquity’ - a fancy word for attraction through closeness.

Other dating apps followed suit, each iterating on the same principle: “We’ll help you meet someone nearby.” From Hinge and Happn to Bumble, these platforms embedded maps into love lives, reshaping not just how people met but how they moved. Tinder Passport, Bumble Travel, Grindr Roam: suddenly your love life could start before your vacation did. Suddenly, every layover held potential, and solo trips felt a little less solitary. Travelers started planning itineraries around potential matches, proving location data's power extended far beyond simply finding the nearest coffee shop.

And that brings us to Zenly, quietly threading the needle between these categories.

Launched in 2011 but peaking in the late 2010s, Zenly wasn’t about dating or group meetups. It was about seeing your close friends on a map in real-time. Animations, cars, pings, emojis - Zenly made the map feel alive. It wasn’t about social broadcasting; it was about ambient togetherness. Not surprisingly, it boomed until Snap acquired it, shelved it in 2023, and sparked a movement in its place. My guess is Snap recognized something the rest of us were just beginning to understand: the future of location wasn't about going somewhere and telling people about it. It was about being somewhere and letting the right people simply know. If you’re on Snapchat and have used Snap Map, you can thank team Zenly and obviously the PM who retrofitted all of this in the native Snapchat app. Just letting y’all know, I despise Bitmojis with passion.

So, the 2010s? They weren’t just about one kind of location-based use case. They were about three overlapping threads:

Groups: organizing around shared interest and geography (Facebook, Meetup)

Dating: filtering matches based on proximity (Grindr, Tinder, Happn, Bumble)

Friends: staying ambiently connected through live maps (Zenly)

Interestingly, while flashier startups rose and fell, Apple's Find My quietly became the silent giant of location sharing. Originally envisioned for parental supervision, it found an unexpected audience with Gen Z and Millennials, transforming into a quiet symbol of trust and intimacy. In Europe, particularly, where privacy anxieties run high, Apple's reputation for data protection made Find My the preferred option over more open platforms like Snap Map. This wasn't about badges or social scores. It was about quiet reassurance. End-to-end encryption meant only intended recipients could see your whereabouts; not even Apple. Unlike gamified apps pushing constant updates, Find My offered a passive, opt-in experience. You could check in on friends without feeling the pressure to performative sharing.

Of course, this convenience wasn't without its wrinkles. Some users reported feeling overly monitored or pressured into constant location sharing. The very design meant to foster safety and connection could, at times, blur boundaries and create unintended social anxieties. It highlights a core tension in location sharing: the desire for reassurance versus the fear of surveillance. This forces a personal reckoning: do we value the reassurance of knowing, or the privacy of not being seen?

What’s Happening Now: The Old Guard Tries Again

Now, in the 2020s, something fascinating is happening. The original makers of social apps who helped break the internet are now trying to fix it.

Ev Williams (of Twitter and Medium) is launching Mozi, a plan-sharing app focused on private meetups. No feeds, no photos, no likes; just encrypted notifications about nearby friends. It sounds a lot like serendipity-as-a-service, aimed at reviving offline spontaneity.

Dennis Crowley, yes, the same one from Dodgeball and Foursquare, is testing BeeBot (formerly Marsbot). It’s an audio-first city guide for your AirPods that uses Foursquare data to whisper location-aware tips as you walk around. He calls it a poor man’s AR. The bet? That audio might be less creepy than dots on a map, especially with the right privacy toggles.

To top this avenger end-game style return, the original Parisian crew that made Zenly has rallied under the banner Amo, determined to prove that friend‑finder maps still have magic if handled with care. In late 2023 they rolled out three tightly linked apps: ID, a collaborative 3D‑sticker profile canvas; Capture, a shared camera‑roll for your inner circle; and Bump, a true “Zenly Lite” that revives knock‑knock pings, one‑hand zoom carousels, and granular privacy toggles. Their pitch is simple: recapture the delight and serendipity of social maps without the teen‑drama and oversharing.

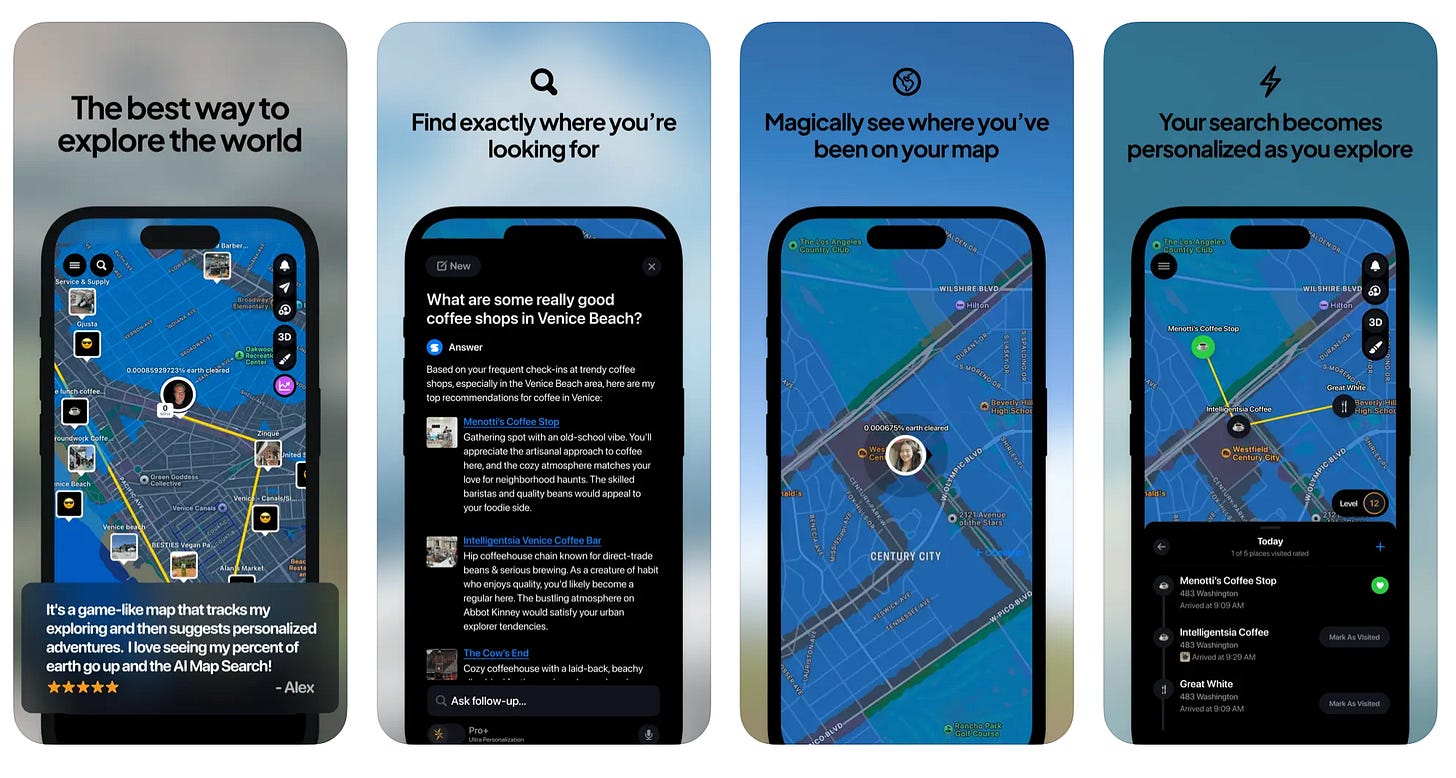

And if this was not enough, a parallel movement marrying checklists with maps for niche communities has too emerged. Beli, launched in July 2021 by Judy Thelen and Eliot Frost, turned restaurant discovery into a campus sport; here users log and rate every meal, earn personalized “Rec” and “Friend” scores, and even compete in Dining Hall of Fame leaderboards across 187 universities. And Superlocal has been quietly doing something similar since mid‑decade, auto‑documenting your journeys with its “Fog of World” overlay and then using machine learning to serve up hyperlocal spot recommendations gamifying exploration into a living, breathing travel journal.

Together, these vertical hybrids hint at the next frontier: maps that don’t just show you where your friends are, but curate experiences, guide adventures, and respect your privacy.

What ties these together isn’t just nostalgia or gimmickry. It’s a quiet but persistent cultural mood: the urge to return to how things used to be. Social apps were meant to make us feel connected, but often left us lonelier. People are increasingly looking for tools that help them meet organically again. Even dating apps are in decline, with more users citing burnout and a desire for offline serendipity.

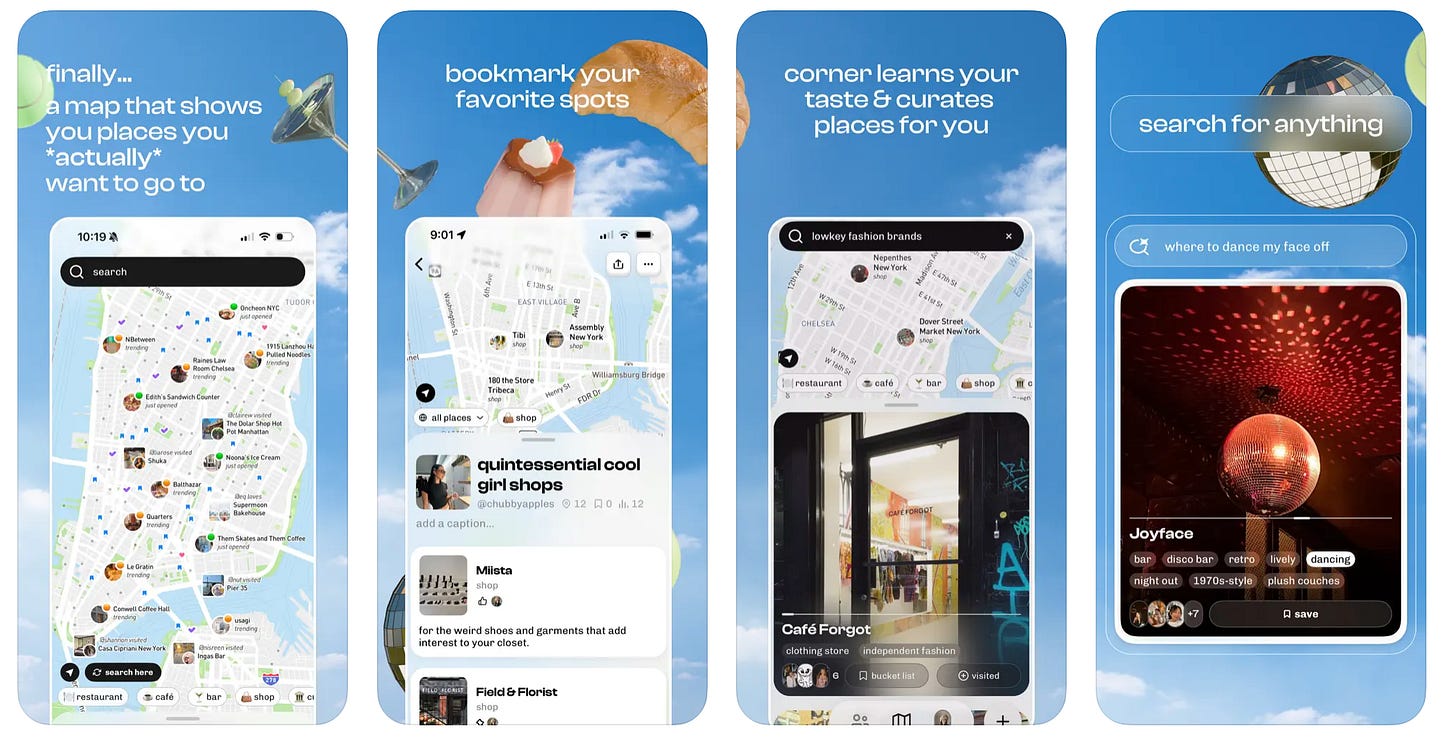

One fascinating app within this landscape of ‘we’re gonna make maps cool, again’ group is Corner. It emerges as a standout with its design-forward approach to social mapping. Conceived by Eliza Wu and Jake Xia, Corner flips the typical review model on its head. Instead of a deluge of anonymous opinions, users pin only their cherished spots – a beloved cafe, a hidden record store, that perfect park bench - creating curated maps that are deeply personal. It’s less about 'what’s good?' and more about 'what I love?' I think over the last few years the world has suddenly woken up to curation as a core part of their personality and want to recommend more and this is where Corner’s strength lies - in its quiet curation, allowing users to share their taste universes with friends. In a sea of algorithmically generated noise, Corner feels like a carefully designed letter from a friend, a reminder that the most meaningful recommendations are often the most personal or another way to say that is: taste isn’t scalable.

So the new wave of apps is doing something the old ones never did: listening. Not just to location pings, but to social exhaustion.

From Coordinates to Context: Where We Go Next

If location-based apps were meant to be the next great canvas for social connection, why did so many fade into irrelevance?

The problem wasn’t with maps. It was with how we designed the social spaces around them. Proximity alone isn’t meaningful. As Alex Kehr once noted, location isn’t the hook. People are.

We fell into the "place discovery" trap: the assumption that if we surface better restaurants or trending events, meaningful interaction will follow. But most people don’t open a map to find places, they open it to find people.

Apps like Zenly and Snap Map worked because they mimicked real-life presence. They weren’t about shouting into the void but about feeling near someone. Like a heartbeat in your pocket. And I guess this why dating apps won the attention game. Not only did they tell you about someone single who lived two miles away but they used location to collapse friction.

Even Google Maps has quietly become a social network, not through feeds but via random reviews, bad photos, and deeply personal breadcrumbs. That’s what serendipity looks like in the wild. Imagine, while cruising Google Maps, you stumbled upon a hidden alleyway on Street View and bam! No, its not a Snorlax but a Song. A pixelated music note flashing like a GTA San Andreas Easter Egg. That's where Soundmap - a location-based game that turns real-world exploring into a quest for musical "drops” is reinventing this play with a surprising 70% of users going solo on their musical scavenger hunts. Proof that sometimes, the most engaging social is when it's just you, the map, and the music.

So, we don’t know where these maps will take us. And, that’s funny because…..duh?

But the future of location-based social apps is clearly not about showing where people are. It’s about collapsing the distance between us.

Less about check-ins. More about connection.

Less about the destination. More about the context.

Or, maybe just say hi to that weird chap who's rumbling through his keyboard and shying away.

we have some big news coming for superlocal next week 👀

loved this articulation, Shivam!